With Reg Z enforcement scuppered, regulators and consumers may not know the true extent of BNPL’s reach for the foreseeable future. In the shadow of a looming recession, that could be dangerous.

Buy now, pay later (BNPL) giant Klarna announced this week that its net losses doubled in Q1 2025 compared to a year earlier, driven by souring consumer loan repayment figures and growing concerns about household financial health, especially in the US. Customer credit losses increased 17% to $136 million, contributing to net losses of $99 million over the quarter.

Though Klarna says it can “respond rapidly to evolving market conditions” — assuaging investor worries as it waits to resume IPO activity — it’s hard to gauge what those sector-specific market conditions are. BNPL lacks a central data repository monitoring the quantity and quality of loans the way other products do (think credit cards, mortgages, and more). While BNPL is still a fairly small subsector, and most loans are relatively small, this systemic nescience renders BNPL a “phantom debt,” as Wells Fargo economists put it in 2023. Add into the mix the Trump Administration’s deregulatory zeal, recently reneging on the CFPB’s enforcement of BNPL under Regulation Z, and things feel even more like entering the Labyrinth.

But BNPL isn’t completely inscrutable. It functions more like Plato’s allegory of the cave, with its reality refracted indirectly and occasionally through earnings reports — as well as credit card amortization. Dr. Benedict Guttman-Kenney, Assistant Professor of Finance at Rice University, found that the use of credit cards to pay off BNPL debt is one way to (imperfectly) gauge the size and state of BNPL. Fintech Nexus interviewed Guttman-Kenney on the relationship between macroeconomic conditions and BNPL’s sustainability, what regulatory shifts mean for the industry, and the long-term potential consequences of BNPL’s lack of data transparency.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How have recent market changes affected the BNPL space?

We’ve seen Klarna postpone its IPO less than a month after launching, and so it’s really uncertain what’s going to happen next with that. That’s definitely a big negative signal: It’s presumably pausing because it thinks that listing now is not going to get as high a price as if it listed a month or two prior.

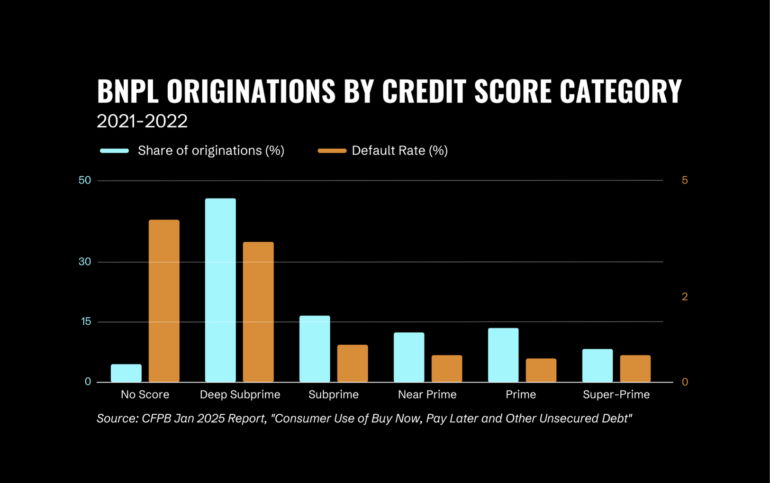

The other kind of negative signal that I kind of see out there is Affirm’s stock price, well down from its peak. If you look at Block, which owns AfterPay, that’s similarly down. So definitely, the market isn’t super confident in where these firms are heading. That’s kind of not surprising, right? It’s like, if we think that spending is going to be going down, if people increasingly think we might already be in a recession, these business models really rely a lot on spending volume. They need to have a lot of volume to generate enough revenue to cover their cost, so that’s definitely the big challenge. The other thing that we’re seeing in the credit card market is that delinquencies are going up, and they’ve been going up for a few months now. We’re also seeing other signs of stress, like more credit card customers only paying the minimum on their credit cards. So if you’re seeing that on the credit card side, I haven’t seen like new figures for the BNPL side, but I think in the next month or so, we should start to get the Q1 reports, and I’d be pretty surprised if we weren’t also seeing some signed restraining in the BNPL side, because these are going to be often similar customers.

The opportunity for for these providers is, if there’s going to be higher inflation, if household budgets are more strained, the benefit for BNPL providers is more people are not able to pay in full, and they’ll want to smooth it out over a few months, so there’s potentially more consumer demand for these products. The question is whether the BNPL providers are willing to meet that demand, because it might just be too risky. That’s what we see in the credit card market historically — when consumer spending is weakest, default rates are highest. That’s when consumers want to buy the most, and lenders want to lend to them the least, because they’ll often make the biggest losses.

What do you make of the CFPB’s decision to not enforce Regulation Z for BNPL? Does this materially change how BNPL operates in the US?

Not enforcing Regulation Z means that there is not a level playing field in providing information across credit products, and so may distort competition. While the largest BNPL lenders don’t charge interest or fees if you pay loans as agreed, not enforcing this regulation makes it easier for lenders to hide bad contract terms from consumers. It therefore penalizes ‘good’ lenders who are transparent with their consumers, and rewards ‘bad’ lenders who try to trick consumers into paying more. From a consumer perspective, it makes it harder for consumers to compare the cost of borrowing across lenders.

The BNPL industry has actually, historically, been pretty supportive of regulation. They kind of think, Oh, we want to be kind of credible. We want to be somewhat on a level playing field that will actually potentially help our ability to get investors, whereas investors may be more worried about, Oh, how’s this going to be regulated? But regulation adds a huge amount of cost, so I can also see why, if you’re a BNPL lender, you might be somewhat happy, like, you don’t need to go through a costly dispute service, you don’t have to spend a lot of time and resources dealing with regulators with like the CFPB. So you can see why they wouldn’t necessarily be too sad about regulation disappearing. Meanwhile, in the UK, the BNPL firms have kind of been begging to be regulated for years now, where they want to be on the same standard as credit cards as a way to gain credibility.

In your 2023 Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance article, you mention how you gauged net volumes in the BNPL space by tracking credit card use to amortize BNPL debt. Is that still the oblique path you have to follow to understand how much money flows through the sector?

There isn’t really good data out there to do better than that. There’s been good work by the regulators in both the CFPB in the US and the FCA in the UK. They gathered data from the firms highlighting how much lending there’s been in the last year. But those were ad hoc collections; they weren’t month by month or whatever, like we do for credit cards.

There have been a lot of consumer surveys, so we have a much better sense of who’s taking out BNPL loans, and if that’s changing over time. So we know that kind of thing, but we don’t know the richness of how many people are borrowing, how many loans there are, what the patterns of borrowing are, what the delinquency rates are, beyond what’s listed in a firm’s investor reports.

It sounds like, especially on the CFPB’s side, that kind of inadequacy is not going to change anytime soon.

I don’t see them doing any data collections for the next few years on this front, unless something changes. The one area where data is starting to emerge is through the credit bureaus. Some lenders are starting to report some BNPL loans, but they’re not reporting all of their loans, and it’s not all lenders reporting, so it’s hard to interpret what’s there at the moment, but that’s something that hopefully will grow over time, because currently that’s a big gap: We just don’t know how much debt people have, and that’s a problem not just for BNPL lenders, but also a problem for credit card lenders and other lenders, who want to know how much debt an applicant has. BNPL lending is still pretty small, so it’s not like everyone’s got this history, and even the people that do have BNPL loans generally borrow small sums, but there’s definitely going to be a segment of people who have a non-trivial amount of BNPL debt, and that’s just not being reflected in their credit reports, so that can kind of have a potentially adverse effect on lending decisions.

When it comes to something like compliance, obviously it’s segmented according to geography, but does operating under one regulatory regime in one geography inform how a global lender like Klarna operates in other markets?

BNPL operators can do this more easily with their technology; they don’t have all these legacy systems. But there’s increasing pressure in the UK market to deregulate and reduce costs. There’s no discussion at all about abolishing the FCA, but over time, you may see these BNPL lenders, even though they’re regulated in the UK, probably going to be under less regulation than if they were regulated like five or 10 years ago, when they would be spending a lot of effort on compliance.

How will this affect consumer engagements with BNPL providers?

It’s hard to know whether it will get worse or better. But my broad view of the BNPL product is it’s overall better than a credit card for a lot of consumers, because credit cards are hugely expensive. We very commonly see people take on debt on a credit card, and they keep revolving that debt and carrying like 20% APR or they default on it. With BNPL, the downside is relatively limited for a lot of consumers because they’re smaller sums, and if you don’t repay, the first thing that really happens is you just can’t get another BNPL loan, which helps prevent a debt spiral.

What do you make of the move to have tie ups with things like DoorDash or other smaller-ticket items?

If you’re really cash constrained enough to use BNPL for a $10 Domino’s purchase then you’re probably already spending beyond your means, and you’re going to get into some trouble. I mean, there’s some kind of benefit to consumers on larger things, like if you’re hosting a party and you’ve got a one-off bigger purchase. But it’s the consistent use where, at some point, you’ve got to pay for this stuff: Where are you going to find the money if you haven’t got the money now?

You can totally see why these BNPL lenders are having these link ups. It’s another source of revenue for them. You can see on the merchant side, it’s well documented that when you offer these BNPL products, you increase order volume, increase sales, and increase customer retention. These are things that customers like. They like the ability to smooth out payments. And you can see why it increased the order volume, both from the economic side of smoothing out your payments, and on the psychology side, you can see kind of, Oh, I was going to spend $10 on a pizza, now I only need to spend $2 today, I can add wedges or whatever to go with it. If they were just going to be paying for it with cash on a debit card or a credit card without paying interest, then these things aren’t wildly different, so it’s not making a huge difference either way.